The Pleasures and Perils of Kink

By Eva Spijkers, LMFT

Kink is having a cultural moment. From rope workshops to TikTok “aftercare” videos, conversations about BDSM—bondage, dominance, submission, and sadomasochism—have gone mainstream. For many, this visibility feels liberating: finally, a public acknowledgment that pleasure, power, and pain can coexist in ways that are consensual, intimate, and deeply fulfilling.

Yet alongside this celebration, we need an honest conversation about the darker side of kink. Not because kink is inherently dangerous, but because pleasure can easily blur into harm when trauma, power, and consent are misunderstood.

When Kink Heals

For survivors of trauma, kink can be a surprisingly powerful form of healing. Research shows that consensual BDSM does not correlate with pathology; in fact, many kink practitioners show lower anxiety and greater well-being than the general population.¹ It’s so important to understand that the intimate space where people enjoy kink, from the bedroom with your partner, to play parties with multiple partners, needs to be trauma-informed in order for kink to be healing. A trauma-informed space means relationships built on safety, consent, and trust. Partners talk openly about boundaries and triggers before anything happens. They check in during a scene, not just after. They treat “no,” “stop,” or a safeword as sacred, because in this kind of space, control is never taken; it’s shared. A trauma-informed space understands that many people carry the echoes of past harm, and that certain kinds of touch, power, or language can easily stir those memories. In trauma-informed spaces, kink allows people to reclaim agency. A submissive who once felt powerless may find safety in a scene where they choose to surrender (and know they can stop it at any time.) A dominant might find catharsis in controlling an encounter that is negotiated, bounded, and infused with trust. Some survivors even use kink as “trauma play,” intentionally revisiting themes of helplessness or control to rewrite their narratives. When handled gently, with self-knowledge, aftercare, and explicit negotiation, these experiences can shift shame into power and fear into arousal.

When Kink Harms

But the same dynamics that make kink potentially healing also make it dangerous. A scene that mirrors past abuse can reactivate trauma instead of releasing it, especially when a partner is unaware of a trigger or dismisses a safeword.

Studies of kink communities reveal three main sources of harm:

Retraumatization and dissociation—when a person disconnects from their body or emotions during play.²

Consent violations—intentional or accidental breaches of limits, often under the guise of “testing boundaries.”³

Physical injuries or risky practices—especially choking/asphyxiation, which carries serious neurological risks even when “done safely.”⁴

And because kink is stigmatized, victims of non-consensual acts within BDSM often struggle to seek help. They fear not being believed—or being told, “Well, you asked for it and wanted this.”

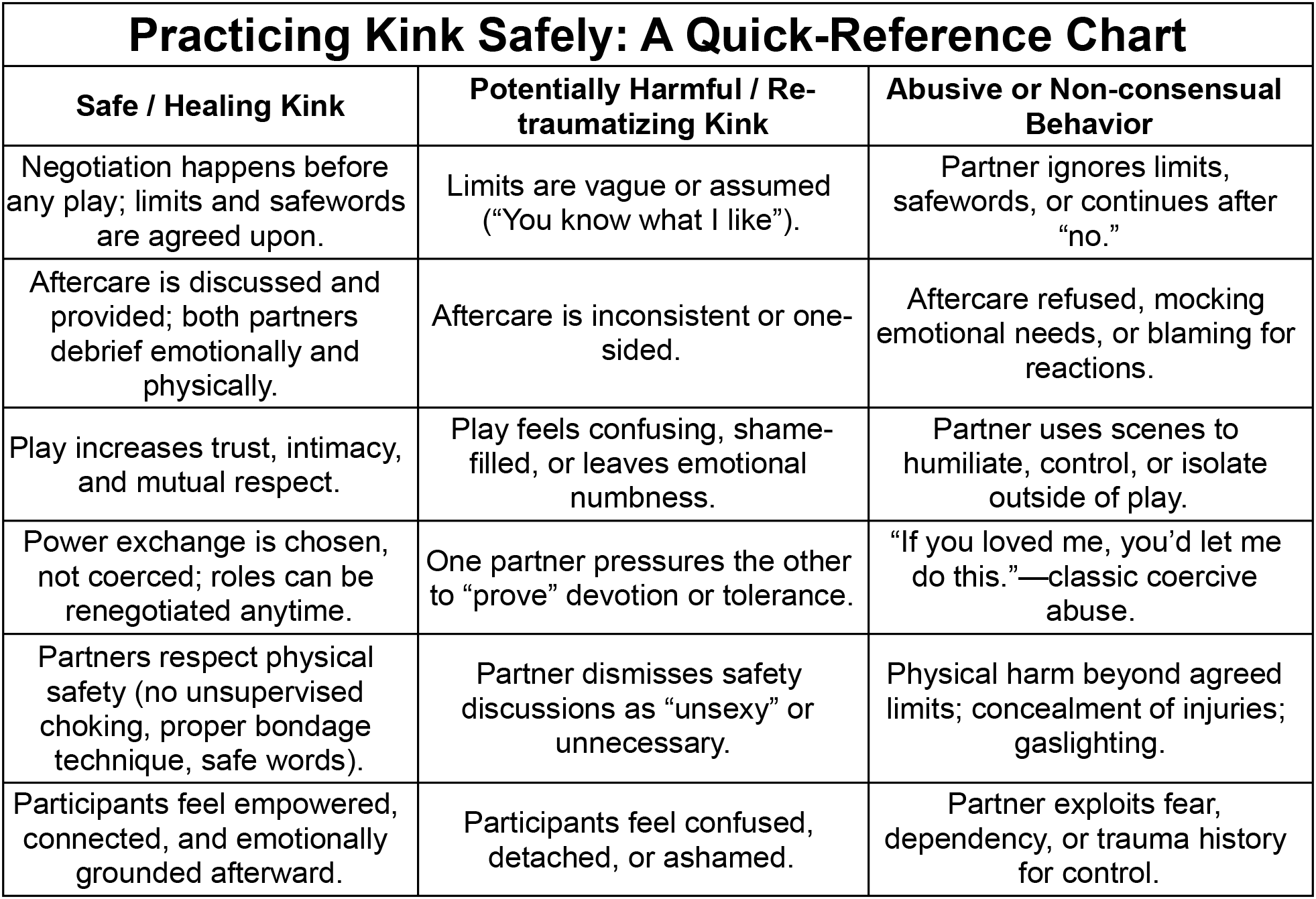

The Line Between Play and Abuse

The defining line isn’t pain, power, or taboo; it’s consent, trust, and emotional safety. Kink is not therapy, though it can be therapeutic. It is not abuse, though it can be abused. What keeps it ethical is mutual, informed, ongoing consent. Everyone involved should have the freedom to say “no” or “stop” without punishment or guilt.

Why This Matters

Kink is a practice that’s more than just fun; it’s powerful. Every scene is built on trust, vulnerability, and emotional risk. When approached with care and understanding, kink can transform pain into pleasure, fear into empowerment, and distance into deep connection. It can teach communication, trust, and empathy; the same ingredients that make any healthy relationship thrive.

But that power cuts both ways. Without a real understanding of consent, trauma, and safety, kink can just as easily reopen old wounds or create new ones. What feels thrilling in fantasy can become confusing, violating, or even traumatizing in reality if practiced without education or respect for limits. Too often, people rush into kink without learning its language—how to negotiate boundaries, use safewords, or de-escalate intense emotional reactions—and end up mistaking harm for intensity or control for care.

Before exploring kink, it’s essential to study it the way you would study fire: with curiosity, respect, and awareness that it can both warm and burn. Pleasure and pain live closer together than we’d like to think, and understanding that fine line (the difference between consensual power and coercive control) is what makes kink not just erotic, but ethical.

References

Connolly, P. H. (2006). Psychological functioning of bondage/domination/sadomasochism practitioners. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 18(1), 79–120.

Gewirtz-Meydan, A., & Godbout, N. (2024). BDSM and childhood sexual abuse: Potential for both repetition and healing. Archives of Sexual Behavior.

Bowling, J. et al. (2024). Reporting consent violations in U.S. kink communities. Journal of Sex Research.

Schori, A. et al. (2021). Fatal outcomes in BDSM: A forensic review. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology, 17(3), 419–428.